My team’s work with Volkswagen on an autonomous driving simulation environments just turned into a new Azure Well-Architected page, which makes this a good time to add some behind-the-scenes commentary from real world experience. The architecture recommended there came from a lot of discovery and experimentation work, and suits quite a broad case that I think is not well represented (yet) in cloud computing products.

The challenge

Testing and CI-style validation in autonomous driving development are a tricky challenge. See, an autonomous driving simulation environment is actually composed of several different components, all working together. There is always a system for time synchronization, typically coupled with some kind of data bus that all the other components can plug into. This is where the challenges start:

- Each component is a separate executable with separate requirements. In our case we had both Windows and Linux components, several of which needed exclusive GPU access.

- Exactly which components you need for a test is totally dependent on what part of the autonomous driving system you’re testing. For example, a lidar sensor dev team needs very high fidelity models of objects it might be detecting. Reflective and absorbtive properties and shape require a lot of detail. So do weather conditions as far as visual occlusion and light scattering effects go. They don’t need much of a road surface simulation, or pedestrians, or other drivers. The dev team working on the highway control component however, needs a totally different set of components, practically mutually exclusive.

- Even within one team the components may vary, as lots of this stuff is non-deterministic. It sometimes helps to validate against more than one simulation of the same environment.

- Components have hard and complex interdependencies, despite separate execution environments. For example, Linux and Windows based components may work closely together to simulate other cars and their drivers’ behaviors. This impacts startup order, where some tools can’t even start initializing until others - or until certain sets of others - are reporting ready. The whole simulation of course, can’t start until everything is ready. These tools are designed to start and operate in a highly stateful manner.

- Because we’re dealing with human lives and liability here, each component needs to be independently validated and verifiable, starting from a known good state. Five years later, we need to be able to reproduce as closely as possible the starting point of the simulation. “Formal Reproducibility” would be amazing, but depends on component development too much to be within our control.

- Finally, some components are designed for human UI interaction. For example the test runner, which has its own system of debug breakpoints and step debugging that can’t be replicated in code (“break when the car is < 2m from the obstacle, or after 68000 virtual milliseconds”). Developers rely on this kind of debugging to build.

Anyone with DevOps engineering experience probably looks at that laundry list and thinks “may as well wish for the f@#$king moon while you’re at it.” I urge a bit more empathy. Remember, these developers are working with non-deterministic code to handle non-deterministic environments. This is not trivial stuff.

A platform for automated driving simulation needs to address those problems. Put another way, the system needs total composability and the ability to model a directed acyclic graph for startup and execution of the simulation; the components need flexibility in OS and interactivity.

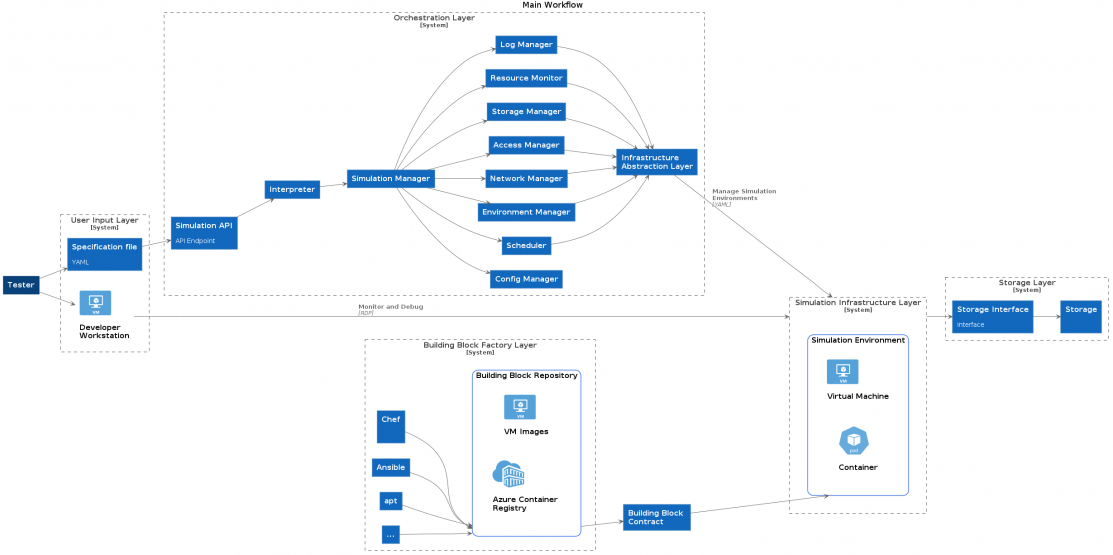

My team came up with this (admittedly complex) diagram to describe the problems in abstract.

Go ahead and zoom in for a better view, it’s a lot to take in. It’s easiest to look at the big segments (“layers” in the parlance of the image): User input, Orchestration, Building Block Factory, Simulation Infrastructure, Storage. Most of these are self explanatory. The building block factory is whatever system creates and validates components, the “building blocks” of any simulation run.

The workflow in the above system is straightforward to describe:

- The developer submits a human-readable document to the UI, which validates and passes it to the orchestration layer. The orchestration layer.

- The orchestration layer interprets the document and provisions the necessary resources - whatever they may be - in an appropriate networking, monitoring, and storage context. The resources themselves come from the Building Block Factory, so they’re all validated and conform to a documented API (the “building block contract”). The provisioned, started components in their network etc frame form the Simulation Infrastructure Layer.

- The simulation runs autonomously, as far as possible. At the end of the simulation, outputs and logs are in the Storage Layer, and the Simulation Infrastructure Layer is deprovisioned.

Just three steps. But the number of boxes and lines in that diagram belie just how complicated it is, on the inside.

The key to the whole system is clearly in the Orchestration Layer. There are great options for the Building Block Factory in most any CI/CD and versioning toolkit. The infrastructure layer is provided by the cloud provider. But this bit of interpreting the user input into a complex graph of components, starting them, monitoring for readiness, then starting execution… that’s hard to find in a single tool.

Some parts of this problem space are well handled by a variety of tools. Provisioning and tearing down cloud resources, for example, could be done through any number of tools like Terraform, or even straight up ARM (Azure Resource Manager) templates. But then what monitors component startup state, managing that directed acyclic graph through to readiness? We evaluated several options for core technologies around which we could architect, including Puppet/Chef, Ansible, Terraform, and a collection of Azure services held together by Azure Functions and duct tape. The clear winner by a substantial margin was Kubernetes.

This was a suspicous conclusion for us, a team of infra specialists. We always have to be careful about our own technical biases, especially towards the new-and-cool tools in our kit (Had Nomad existed at the time it probably would have been a good contender, and made us feel a bit better about having at least two alternatives). But however you cut the problem, Kubernetes out of the box solved almost all of the problems in the Orchestrator Layer space, and provided a great starting point for the remaining boxes.

The boxes that Kubernetes does not cover OOTB, are the flexibility to run VMs or containers interchangeably (with an abstraction layer to ensure identical APIs), and the monitoring of buildup and simulation start/end.

There are a number of projects to provide the former, including integrations into Azure, and our choice, kube-virt. Importantly for us at the time: kube-virt was an earlier stage CNCI project and therefore still rough around the edges, but it was already a supported part of Azure RedHat OpenShift, and the supported way to run Azure IoT Edge on Kubernetes.

The latter problem is the core business logic, so it is the Right Focus for Custom Code. But even there Kubernetes gives us a good start, as it is already an event-driven architecture with deep connections to container lifecycle and readiness/liveness probes. What’s more, the model of Kubernetes objects and controllers already implements the concept of a larger object abstracting a group of lower-level ones, in Deployments.

In fact, we found that our custom controller would have to implement a CRD quite similar to a Kubernetes Deployment. We could even extend the Deployment object to do it. The user ultimately could provide a simple YAML like this:

name: my simulation run

spec:

start:

component: test-runner

command: C:\start.exe

components:

- name: sync-server

image: sim/sync-server:5.4-dev

- name: test-runner

image: sim/test-runner:3.2.2

interactive: true

- name: environment-sim

image: sim/vtd:2.1

requires:

gpu: 1

depends:

- test-runner

- sync-server

results:

storageClass: AzureBlob

Given some metadata on each component, this is probably sufficient information for a controller to create the required deployments and run the simulation.

test-runneris a Windows VM image, as indicated by the component’s own metadata. Theinteractiveflag indicates that the controller should return a proxy to the RDP port on the VM.- Other components are both containers.

- One container shows a resource request for a gpu core, which is handled by assigning the container to the right node pool.

- That container also declares its’ dependencies. Probes are defined in the component metadata; the kubernetes controller watches for both dependencies to pass their Readiness probes, and then starts

environment-sim. - Once all three components pass their Readiness probes,

spec.start.commandis run insidespec.start.component. When the command terminates, the simulation is considered complete. - The

spec.resultskey helps the Controller create a PVC for results. The actual PVC is later accessible through a well-known naming scheme, such as[datetime]-[name]. - Component definitions include default ports to expose, but by default nothing is exposed to the outside world.

Of course the actual Deployments and/or Replicasets involved need a lot more information than this. But that information is all consistent enough between runs that it can be templated with default values. The structure of this CRD is similar enough to other Kubernetes objects, that we can allow the user freedom to add other keys from the container spec, for example, to override those defaults. The 99% case however, would profit from opinionated defaults.

Implications

If you’ve followed along this far, you’ve noticed that this domain is not unique to automotive simulation. Lots of computational problems require a directed acyclic graph for building up interdependent components, with a defined execution and teardown afterwards. But execution automation tools like batch runners rarely offer the kind of composability that has become the norm in service-oriented infrastructure. The key insight that this approach offers, is that an event-driven architecture for managing infrastructure, like Kubernetes, has a lot to offer in discrete computational tasks as well. This is particularly the case in very domain-knowledge heavy areas like simulation, but probably also in data science, IoT, biochemistry, and others.

This diagram, architecture, and first steps with a commercial customer were only the beginning. I’m no longer on that project, but I look forward to seeing how it develops.